Couverture du livre « Enquête sur les modes d'existence. Une anthropologie des modernes », de Bruno Latour, 2012.

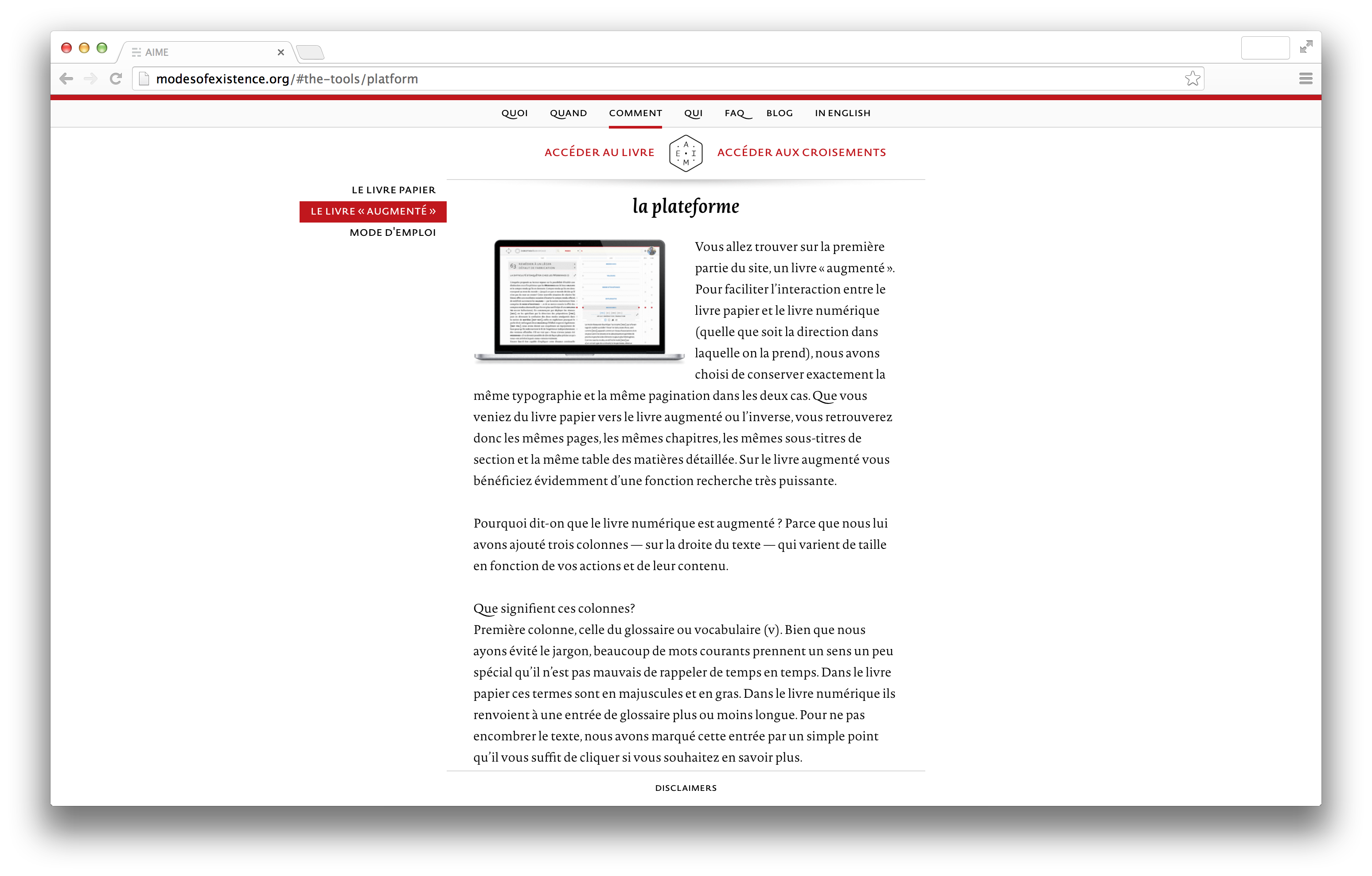

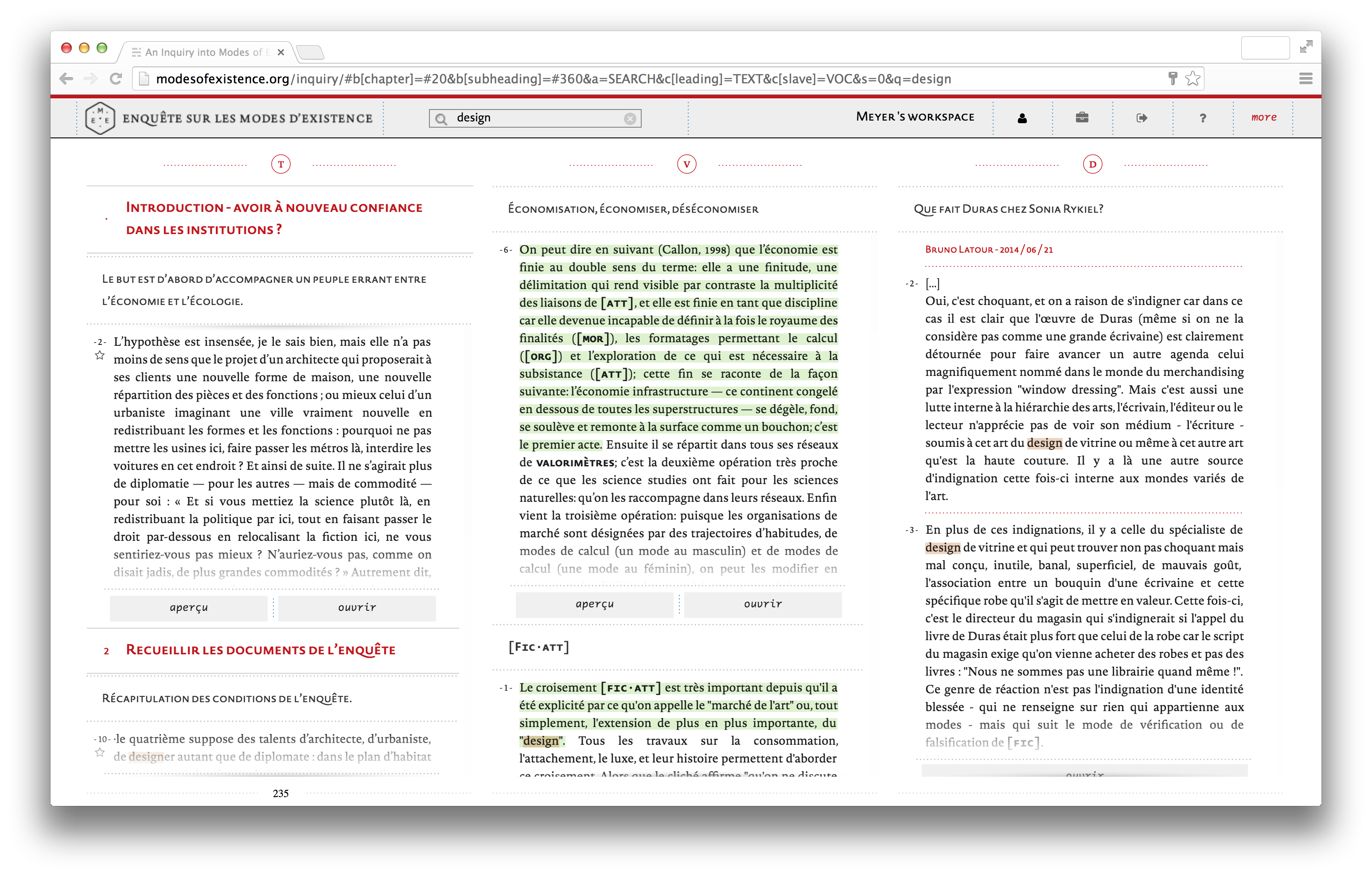

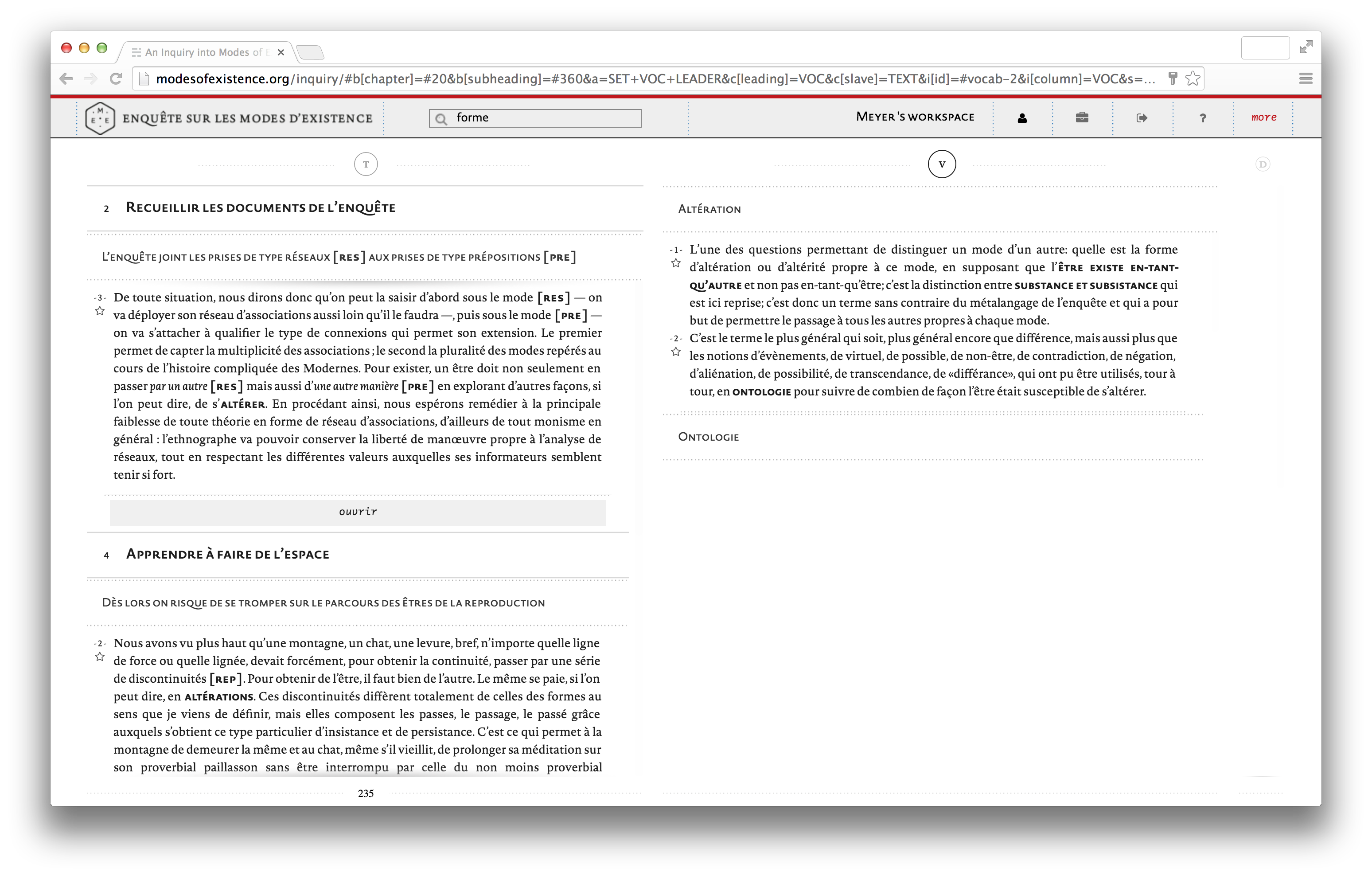

Capture d'écran de la plateforme AIME (« An Inquiry Into Modes of Existence »), version augmenté du livre. Voir : modeofexistence.org

A collaborative project to build an open-ended repertoire for humanistic research, indicating a new symbiosis between digital environment and argumentation.

Bruno Latour’s works – inextricably linked to Actor-Network Theory and the development of the sociology of science – have always focused on innovation in methods, subjects, and languages of social sciences. Examples include : his exhibition « Iconoclash » and its attendant research, which investigates the role, power, and status of icon-images as tools of war ; an article on Gaston Lagaffe, in which a famous comic strip by Belgian artist Franquin is used as an expedient for exploring the principles of sociology and technology ; and Aramis ou l’amour des techniques, a science-fiction book on the failure of Paris’s rapid-transit system.

His latest project, AIME : An Inquiry into Modes of Existence : An Anthropology of the Moderns 1 The project is financed by the European Research Council., is even more ambitious in terms of content – metaphysics –, method – an open enquiry – and tools – digital and non-digital. As a preliminary result of over twenty-five years of research, AIME describes, analyzes, and critiques the practices that make up different aspects of our realm – law, religion, science, and art – which Latour considers modes of existence, or rather metaphysical descriptions based on empirical experience.

Although empirical metaphysics might sound like an oxymoron at first, with AIME it becomes a field research method. For Latour, the only strategy for describing these various modes is to observe them in action and, since each considers its own practices and needs exclusive, their moments of interaction become a privileged area for investigating their being 2 To date the project has identified 15 modes of existence, a contingent, provisional number.. For example, he documents using the movie « Timbuktu », directed by Abderrahmane Sissako, the difficulties in disentangling the Religion and the Politics modes 3 See online.. The construction of this documentary repertoire, the description of these modes of existence, and the potential discovery of new modes are entrusted to an open and collaborative research, conceived as an ambitious experiment in digital Humanities.

Formats and arrangements

The project involves three phases : the first allows researchers to become familiar with the various modes; the second, opened to other researchers, encourages extensions of and modifications to the documentary repertoire; the third relates to negotiation between the various modes. The first two phases took the format of a report and a digital working platform, respectively.

The AIME report is an unusual format for a philosophical research since it conceptualizes the modes and their interactions in the most condensed, lightest way possible, with no notes, glossaries, or bibliographic references: it is a guided semi-fictional account of the journey in the research, bringing into the printed matter only some links to the critical apparatus.

The report is the digital platform’s antecedent, and in the latter readers are invited to explore, critique, and expand upon the entire enquiry, thereby collaborating with the project’s main researchers. In the report a few keywords and the acronyms of each mode are graphically emphasized to indicate points of entry into the digital platform. The platform has two instances. In the first one, the enquiry elements are organized in adjacent columns that progressively expand on the content proposed by Latour. The first column features the text from the report; the second is a glossary that contextualizes some key concepts as they relate to other authors or philosophies; the third brings all the research documents and evidencies together; and, lastly, the fourth collects the contributions on all the previous columns. In this way readers can start with any of the four columns and horizontally expand their reading to weave their own personal narratives.

The column of documents is particularly revealing, both in the economy of its contents and its use of multimedia elements. The documents describe all kinds of manifestations as the product of a mode of existence, and are accompanied by an interpretative text and indexical reference ; a series of documents relating to a single point in the column of text or the glossary is considered the stage setting 4 The term stage setting (scenografia) is understood here not in the usual sense of a scene’s backdrop, nor does it play a mimetic role. Rather, it refers to the possibility of reconstructing the entire scene, actors included. of a textually philosophical instance.

A preliminary series of stage settings was gathered from sources outside the project as an initial basis for reflection. More specific contributions were then produced by photographers 5 Specifically, Armin Linke has made his entire photographic archive available, and (with the contribution of his students at the HfG Karlsruhe) has produced approximately ten original reportages., video-makers, and artists charged with the task of capturing the essences of the various modes in their more subtle nuances.

To further explore the ductility that the digital offered, a transversal, inhomogeneous and non-linear way to display the information has been conceived. This second instance of the digital platform has been developed with the scope of portraying the enquiry from a point of view external to the author’s one. Here, the sequential nature of the book has been left out to produce a navigation system were the modes of existence and their crossing are considered as territories to be experienced chorographically 6 Chorography is the art of describing a region, and by extension such a description or map. Richard Helgerson states that « chorography defines itself by opposition to chronicle. It is the genre devoted to place, and chronicle is the genre devoted to time ». A chronicle description of the enquiry, in this sense is the book, offering the author’s journey into it. along with their folklore, myths, cultures, climates, situations, and histories. By selecting a specific mode or crossing the user is confronted with all the fragments – text paragraphs, documents, contributions – that are attached to it, composing a scattered, but extremely qualitative, representation of it. The different fragments can be assembled, then, to compose personal scenario, a sort of re-invention and extension of an analogical device called common place book, assembling a personalized arrangement of working elements facilitating reflexive thought. 7 The use of the common place book has been firstly described by Jon Locke and Robert Darnton provides us with a clear insight about their role from 1700 onward : « Unlike modern readers, who follow the flow of a narrative from beginning to end [… early modern Englishmen read in fits and starts and jumped from book to book. They broke texts into fragments and assembled them into new patterns […]. Then they reread the copies and rearranged the patterns while adding more excerpts. Reading and writing were therefore inseparable activities. They belonged to a continuous effort to make sense of things […] ». Darnton, Robert, « The case for books : Past, present, and future », PublicAffairs, 2009.]

The atmosphere of AIME interfaces is substantially different from the layout and structure of an encyclopedia, in the sense that its scope is neither illustrative nor pedagogical. 8 John Bender and Michael Marrinan, « The Culture of Diagram, Stanford » : Stanford University Press, 2010. None of the documents are produced from an all-knowing perspective capable of organizing documents and stage settings into preset tables or charts. AIME’s repertoire is therefore neither a finished collection nor a catalog of subjects to be reinterpreted as an informative digital collage : both approaches would negate its fundamental nature as an open, collaborative research project.

The AIME interfaces, both the digital and non-digital, are designed to help researchers and readers play an active role reinterpreting and rewriting the documents, as well as to elicit them to fill in missing elements. This leads to the creation of diagrammatic lines connecting visual fragments and textual elements on a topological environment. Moving between the columns, lining up information, scrolling through the stage settings, composing different scenarios, users create temporary informative orders, hybrids between image and text, in which they can hypothesize, deduce, or refute the project’s philosophical arguments.

Archives and arguments

From a archival point of view, all the documents underwent a process of referentiation that allowed their inclusion in a database. The procedure of separating informative content from its material form and its formal presentation allows for a flexible, dynamic visualization of all the documents and how they’re linked to the various open, temporary display configurations. This cycle – wherein the document is separated from its original environment, digitized, inserted into a database, and finally presented anew in a different environment – 9 N. Katherine Hayles, « How We Think : Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis », Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2012. suggests that the dichotomy between cultural forms of the database and cultural forms of narration is outmoded, regardless of the fact that the former seemed likely to triumph over the latter 10 Lev Manovich, « The Language of New Media », Cambridge MA : MIT Press, 2001.. AIME unites the document-based repertoire, understood as a database, and the specificity of narration, understood as empirical evidence, in a natural symbiosis that recalls the activity of archiving as discussed by Lydén 11 Karl Lydén, « Archive » in Zbyněk Baladrán and Vít Havránek (eds.), « Atlas of Transformation », Zürich : JRP-Ringier, 2010.. It isn’t the enormous quantity of data that has the effect of sublimating the reader, nor is it those data’s quality that turns the reader into an archivist : rather, the mechanism of the archive itself is what leads readers and fellow researchers to arrive at philosophical inferences, thus re-installing the unique savoir-faire of Humanities into a digital mediated domain.

Contexts ans networks

Although, many have argued that digital humanities 12 « Digital Humanities is not a unified field but an array of convergent practices that explore a universe in which : a) print is no longer the exclusive or the normative medium in which knowledge is produced and/or disseminated ; instead, print finds itself absorbed into new, multimedia configurations ; and b) digital tools, techniques, and media have altered the production and dissemination of knowledge in the arts, human and social sciences. », « Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0 », 2009. are reframing the work scholars do in humanities as less consumptive and more curatorial, less solitary and more collaborative, humanities have always been intensely interactive and social, a vibrant ecosystem of shared, reworked ideas as the project Mapping Republic of Letters 13 republicofletters.stanford.edu. has thoroughly highlighted. Far from the cliché of the solitary author, the writing of a humanities’ academic piece of work has always been done with the help of a network of external references (books, data, documents), but also of actual contributors, that is expert readers, intellectual opponents or fertilizers, who have helped the main writer to improve, strengthen and enrich her thesis as it was in the making. Reading one’s argumentation has always consisted in following the author’s path into the complex contextual network of references she has weaved. Therefore, writing and reading in the humanities and social sciences, especially through academic publishing, are activities consisting in unfolding an argumentative content deep-rooted in a specific context, whether it be cultural (through academic apparatus and citation) or social (through the help and interactions with contributors or reviewers). Today, digital means allow us to provide enhanced and enriched materializations of this contextual nature of humanities’ intellectual processes of writing and reading. However, although existing humanities publishing platforms provide ways of saving, accessing and commenting digital content 14 See for instance the french institution OpenEdition : openedition.org., rare are the ones which try to take advantage of the plasticity and richness of screen languages in order to enrich writing and reading experiences, or more precisely questioning the possibilities of digital technology to amplify or to transform these contextual groundings of scholarly discourses’ production and reception. Many are the projects that simply implement multimedia elements or hyperlinked text, as a mere transposition of print-born critical apparatus, without reframing the structure and specific rhetoric of digital argumentation 15 Johanna Drucker, « Pixel dust : Illusions of Innovation in Scholarly Publishing », LA Review of Books, 2014 – online access : lareviewofbooks.org(consulted 1/28/15).. Many are the projects where the interaction with the audience is relegated to a commentary role and not to a real contributive one.

To overcome these limitations, the radical choice has been to reflow the AIME contextual elements preserving their wealth and abundance and not to simply pour its synthetic content into different interface whether based on printing technologies, digital screening or physical meeting. In the project we were not looking for a new surface for a well fixed content but for new ways of experiencing the entire project context. In other words, to break down the content-container hegemony, reversing the traditional publishing paradigm, starting working with the context to develop and maintain rich, linked content. The entire enquiry has been flattened down, resulting in a single and huge network of heterogeneous elements, a technical layer combined with an intellectual method used to generate all the AIME formats produced accordingly to the different moments of the project : a combination of artifacts conceived not as an immutable bricks but as an ethereal and networked system where to distill different modes of reading – ways of approaching these heterogeneous elements – such as paths – texts as a succession of elements forming a narrative, used for generating the report and the first digital interface – or fields – texts as an assemblage of discursive and contextual elements inside a thematic field, used in the second digital interface and in the face-to-face meeting. This capability to produce different modes of reading can induce AIME to be seen as a machine enriching the relationship between writers and readers in producing, amending, archiving arguments. It involves a methodological reframing in the way humanities inquiries are conducted and communicated, whether it be in academic, educational or public contexts. Eventually, it brings intellectual innovation by enabling writers and readers to track the evolution of their work while constantly rewriting and enriching it with contextual elements, disclosing the activities that were almost invisible to the public in print-exclusive Humanities.

Publics and publications

Following the definition of the project given by Bruno Latour, AIME is more a tool than a traditional academic publishing platform: it is not meant to present definitive results, but rather to foster a greater definition of the modes of existence through the practice of the set-up. It presents also the particularity of having embedded some mechanisms to detect and react to the practices and feedbacks of its participants.

By gathering users’ traces on the digital platform (reading metrics, users’ activities such as highlighting or annotating some elements of the repertoire…) and disseminating an online and on-going questionnaire study, such a machine tried to observe and adapt itself as the inquiry was still in process. For instance, through an indeep analysis of the reading metrics of the platform, it has been discovered that the document column was surprisingly under-read by the visitors: thus the choice has been made to highlight more this part of the repertoire through the community management activity of the project. This kind of adjustments and shifts allows to detect some genuine methodological novelties about digital scholarly publishing artifacts regarding print-based ones : first, they give the ability for a writer to actively read the traces leaved by her readers (and thus, change the sense of reading, making the author become the reader of her readership), and second to develop a variety of intellectual strategies thanks to this possibility, such as making the initial argument adapt or react to these diverse feedbacks. As a publication of research, it thus exceeds the role of a mere dissemination of results, because it becomes also an (inter)active tool of observation, elaboration and discussion in the humanities researcher’s workshop, redefining the instrumental potential of academic documents in scholarly work 16 See for instance the french institution OpenEdition : www.openedition.org..

Considered as an open and collective place, AIME also allowed to questions some issues and evolutions about authorship in digital environments. Apart the fact that the initial inquiry was itself based on a dense network of contextual elements, the very methodology of the inquiry was to share Latour’s research with an open community of researchers willing to participate and associate them to the authorship of the project. For that purpose, AIME adopted an expert-review and moderation process dubbed mediation, proposing to a college of experts (chosen for their balanced intellectual distance with Latour’s positions and their intellectual expertise in one or several modes of existence) to review and advise people proposing a contribution to the repertoire before it was publicly readable. The accepted contributions come included in the repertoire, and their writers are cited in the list of project’s authors 17 Johanna Drucker, « Pixel dust : Illusions of Innovation in Scholarly Publishing », LA Review of Books, 2014 - online access : Pixel dust online (consulted 1/28/15).. Therefore, because of its highly-constrained and centralized protocol, AIME, as a collective writing place, is not open as a wiki-like platform or even a plain moderated web forum or blog. But, because of the aim of contributions and the peculiar role of mediators, it is neither a traditional academic peer-reviewed journal or even a curated monograph. With its complex distributed (but not equally shared) authorship, AIME stands with other emerging publishing-related practices in Digital Humanities (such as post-publication filtering or open-reviewing) 18 Zack Coble, Sarah Potvin, Roxanne Shirazi, « Process as Product : Scholarly Communication Experiments in the Digital Humanities », Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication, 2.3, 2014. that develop and acknowledge intermediate levels of authority and legitimacy in scholarly public spaces. It also encourages to rethink the different publishing formats available for academic communication : AIME’s contributions instantiate a peculiar form of scholarly objects, that one could qualify as middle-state publishing artifacts, following the definition installed by the Institute for the Future of the Book’s MediaCommons project 19 See : the Future of the Book’s online., that is pieces of work which are, in quality and mode of legitimation, at the intersection between native web-born objects such as blog posts, and academic contributions such as peer-reviewed journals’ articles.

Designing and opening

Eventually, AIME could be considered as a design project in the sense that it has been, at all times, conceived both as a philosophical endeavour and a unique and specific technical, organizational & aesthetic scholarly device development. This doesn’t mean that the inquiry had been planned or projected from the beginning, using design as a means to promote or stage a preconceived and immutable discourse served by a fully-defined scenario. It neither means that the relations between designers and others have been clearly compartmented and one-sided (designers serving philosophers or vice versa). It is, indeed, a design project in the sense that it has been a constant and mutually fertile experimental negotiation between the different dimensions of the project and their requirements, whether they the one of bibliographical and database technologies, of scholarly interaction design, or of empirical philosophy.

During the 2014 digital humanities workshop « Grenzen überschreiten – Digitale Geisteswissenschaft heute und morgen », Kurt Fendt, executive director of the MIT Hyperstudio 20 See : hyperstudio.mit., praised AIME for its excellence in the field, labeling it « an open-ended research project ». Therefore, the renewed role of designers in this kind of projects could be claimed at the one of provoking and maintaining, through experimentation, an open-ended approach of humanities research endeavors in highly plural digital environments.