Couverture de la revue « Un ambigua utopia », n°1, décembre 1977.

Couverture de la revue « Neural », Post-Digital Print (postscript), n°44, 2013.

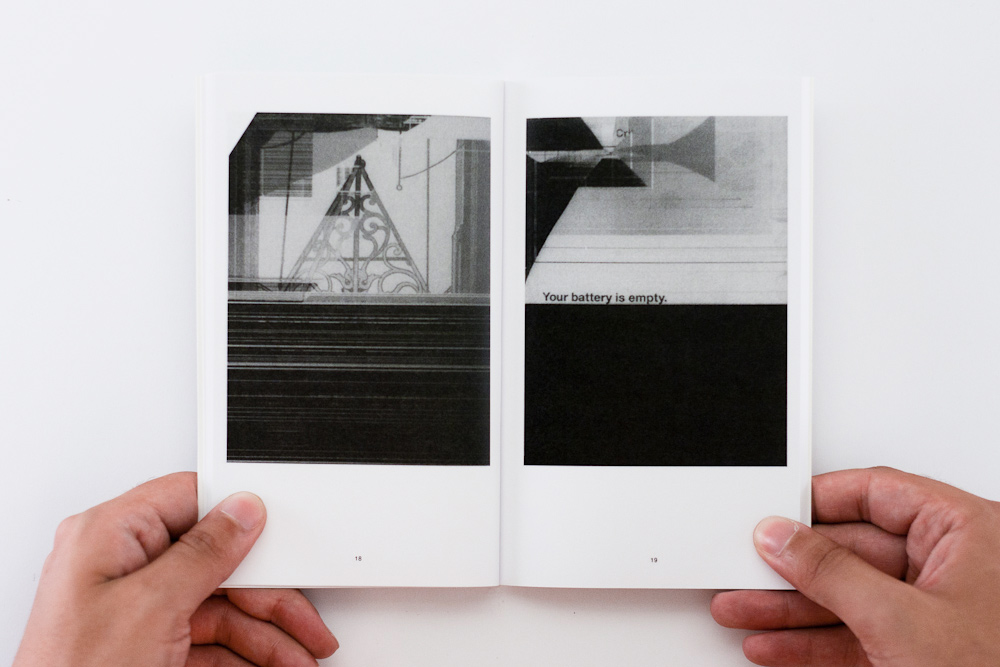

« 56 Broken Kindle Screens », Sebastian Schmieg et Silvio Lorusso, 2013.

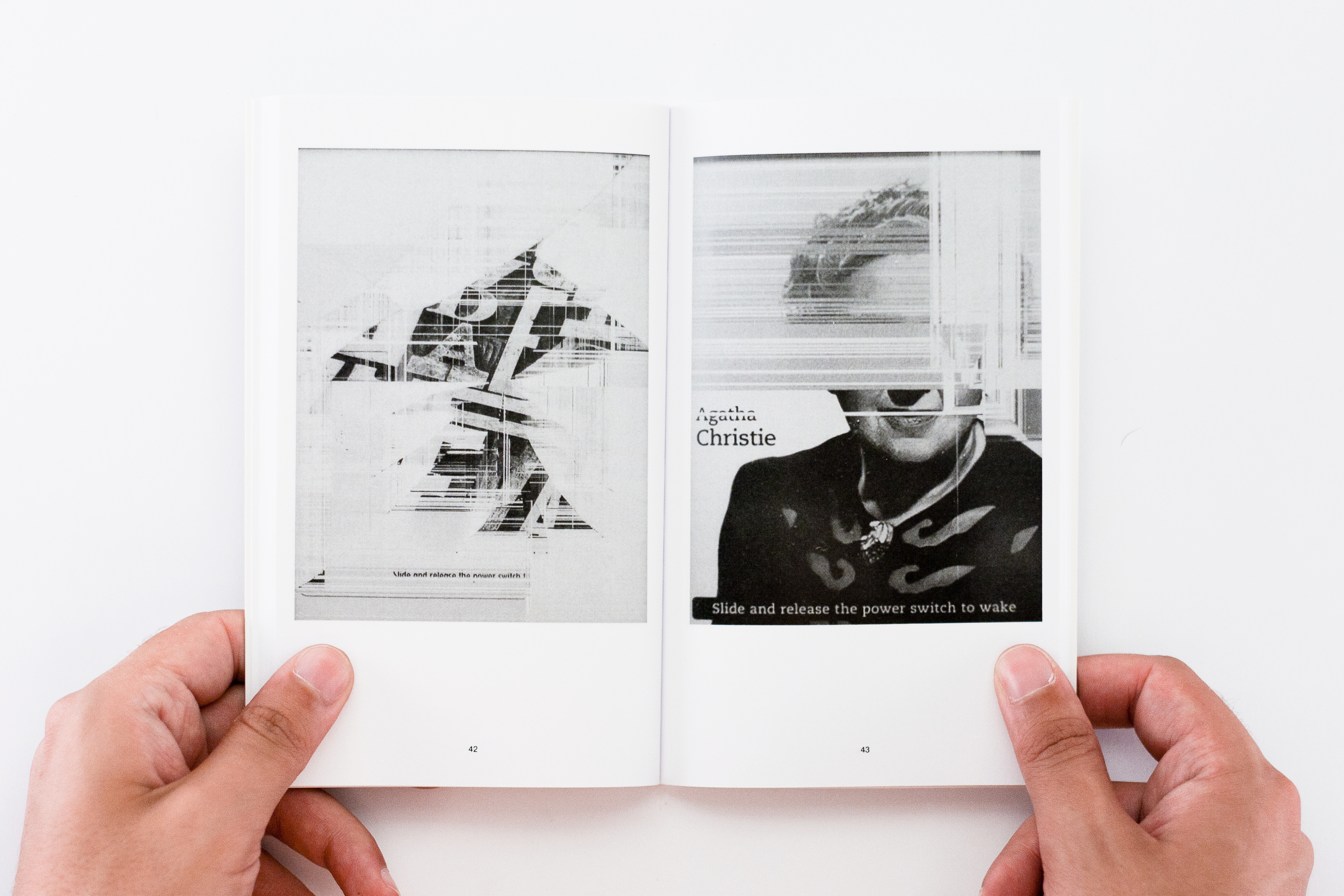

« 56 Broken Kindle Screens », Sebastian Schmieg et Silvio Lorusso, 2013.

The post-digital print era has definitively started. On one side artist’s books conceived around Internet and IT-based processes are flourishing, with a parallel development of a whole taxonomy of techniques and approaches. Further-more public and not-so-public efforts in collectively scanning underground culture in print (sharing the files in proper digital repositories) is revamping the production and the rediscover of critical content in a classic form. On the other side, the unveiling of real Google’s major plan concerning the industrial scanning of entire libraries, the rising of the un-sustainability of newspapers’ business model, the growing role of software in literary and journalistic production, and the constant fine-tuning of commercial e-publications’ rules are slowly changing the industrial print mediascape. The resulting complex scenario helps to shed a new light on the role of networks in these processes, which can finally be questioned in order to be considered not anymore as unavoidable converging medium but instead extremely powerful agents.

Taxonomy of publications scraping information from Internet

In 1981 Italian art historian and curator Germano Celant, wrote in a text for the historical exhibition « Books by Artists » at Art Metropol in Toronto : « artist’s books [...] have contributed to and have themselves affected the continuing process of the “dematerialization of the art object”. » 1 Celant, G. « Book as Artwork : 1960-72 » in « Books by Artists », Art Metropol, Toronto, 1981. This early awareness of publishing potential to dematerialize art (thanks to its medium status and to the preponderant role of language in it) is now completely embodied in the whole dematerialization of publishing practice through the digital. Katherine Hayles precisely describes the dynamics embedded in this process : « almost all print books are digital files before they become books; This is the form they are composed, edited, composited, and sent to the computerized machines that produce them as books. They should, then, properly be considered as electronic texts for which print is the output form. » 2 Hayles, K., « Electronic Literature : New Horizons for the Literary », University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, IN, 2008.

This status has been recently exploited by a new generation of new media artists who have focused on publishing and its promising ambivalence in paper and digital. Consequently, in the 2010s the combination of free content available on the internet in big data, proportions with the inexpensive Print-on-Demand platforms have generated plenty of contemporary artists’ books. They harvest or somehow obtain content from internet and re-elaborate it in a classic book format finalized in a file ready to be printed and shipped.

Artist Paul Soulellis has tried to define this common practice as a sequence of « Search, compile, publish ». Further-more he refers to the whole production of this kind as to the Library of the Printed Web 3 Soulellis, P., « Printed Web #1 », Library of the Printed Web, Los Angeles, 2014. and he attempts to compile a draft taxonomy through three main categories :

« Grabbing (and scraping) ». Here artists perform focused, symbolic or conceptual web searches query, and then grab the typically visually-oriented results, laying them out in a book format. A renown example is Silvio Lorusso and Sebastian Schmieg « Broken Kindle Screens » 4 Broken Kindle Screens 56., where they collect found glitched frozen screenshots taking place on e-readers compiling a visual book with a classic aesthetics of failure.

« Hunting ». Here artists are taking a highly specific screen capture that functions as evidence to support an idea. They’re looking for specific content or results, and once they found some they start to accumulate them till they’ve gathered a meaningful collection. An example here is « a series of unfortunate events » by photographer Michael Wolf 5 photomichaelwolf.com.. He looks for accidents in Google Street View involving people or animals, then he points the camera to the screen and shoot them including the recognizable screen texture and light, which visually unifies the consistent subjects.

« Performing » is about artists trying to make a kind of performance between web and print. A performance with data, or how he put it : « publishing performing the Internet ». Consequently, here some software is usually involved, transforming the found or just public data into an artwork form content-wise, maintaining the book layout and structure within classic standards. « AutoSummarize » by Jason Huff 6 www.jason-huff.com/projects/autosummarize/. fits this definition very well, as he’s using Microsoft Word to summarize in ten sentences the top one hundred most downloaded copyright free books. His performance happens first downloading the content and then using a standard and widespread software function to coherently unifying the different texts into a quintessence of internet users’ popular knowledge, once more in a standard book format.

Hybrids, processual print

In all the previous cases we have an arbitrary narrative, constructed upon the respective selection. And this narrative is employing a specific aesthetics in order to create a visual unity, through the collected data and with the publication standards. Further-more this visual unity is universally recognizable due to the ubiquitousness of online life and visual characteristics in general.

But what they are enabling, in the end, is mainly a transduction between two media: the online and the printed one. They select a sequential or in any case reductive part of the web, and then they mould it into traditional publishing guidelines. Beyond the visual effectiveness of this process, it uses software and networks mostly instrumentally (as a tool) more than as a paradigm to generate new kind of works. What I try to define as hybrid have to perform the networks more deeply, creating what I call processual print.

An early experiment, for example, has been undertaken by Gregory Chatonsky with the artwork « Capture » 7 chatonsky.net.. Capture is a prolific rock band, generating new songs based on lyrics retrieved from the net and performing live concerts of its own generated music lasting an average of eight hours each. Further-more the band is very active on social media, often posting new content and comments. But we are talking here about a completely invented band. Several books have been written about them, including a biography, compiled by retrieving pictures and texts from the Internet and carefully but automatically assembling and printing them. These printed biographies are simultaneously ordinary and artistic books, becoming a component of a more complex artwork. In Capture the software process is able to create a narrative that can be almost universally read, potentially updated at every print (or anytime) and eventually infiltrating some of the alternative music histories, resulting as a future fake reference, accepted and historicized. Its processual nature is then orchestrated by a programmed software, and performed through the networks in its creation first and in its validation after.

Digitising everything

Producing books from online content is only one side of the coin : the other one is scanning existing books and sharing them. Books or magazines can now be quickly reduced to a computer file, especially with one of the many open source models of DIY book scanner 8 www.diybookscanner.org., based on cameras interconnected with network hardware and laptops, instead of their flatbed alternative prone to the slow speed of CCD-based sensors and bottleneck suffering hardware connections. They are then classically dematerialized and subject to their consequently acquired new characteristics. But to quote Jacques Derrida « dematerializing » is « a very deceptive word meaning that in truth they are moving from one kind of matter to another, and actually becoming all the more material, in the sense that they are gaining in potential dynamics » 9 Derrida J., Paper Machine, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 2005.. Derrida is clearly pointing out how misleading would be to consider the digital files of the same quality (in different respects) to the printed one, or as a digestible, eventually even more dynamic version of them.

More-over scholar Bonnie Mak remarks, talking about a digitized version of « Controversia de nobilitate » a text printed around 1450 : « shaped by social forces of the twenty-first century, and marked with cultural, bibliographic, and computational codes of the past and present, the digitized pages are witness to their own course through time and space » 10 Mak, B., « How the Page Matters », University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2011..

To tangibly prove the very specific qualities of the digitized text, we can notice its use in critical artworks which have used the different characteristics of books once converted in a digital form (mainly being automatically searchable and being prone to sampling, cut and paste, and to some extent to a kind of remix) with a purpose.

In « La carte ou le territoire » (The map or the territory) 11 La carte ou le territoire online. artist Stéphanie Vilayphiou selected a controversial book, Michel Houellebecq’s « The map and the territory », which became renowned for its evident quotes from Wikipedia, which both the author and the publisher refused to acknowledge. She used the book’s digitized text with wrote a software filter, which looks for each sentence (or part of it) in the enormous searchable archives of Google Books, finding the same sentences or smaller sequences of words in other books, from whatever author and period. Then she visualizes these found sequences maintaining the scan from the original book in the background, highlighting the searched (and found) text, visually transforming the original book in a digital collage of quotations, loosing even the last bit of originality. Vilayphiou embodies her sharp irony within a functional mechanism, exploiting Google’s industrial collection of texts and smartly expanding the mediating properties of language through the networks.

Not by accident, she selected Google Books to find the references. This industrial and commercial scanning effort by Google, with more than 30 million books scanned, has been recently interpreted and unveiled for its own final goal, which is different from the one commonly perceived. Formally it has been advertised since almost the beginning as the dream of a universal library envisioned by its two founders (Larry Page and Sergey Brin), but it goes much further than that. The movie « Google and the world brain » 12 www.worldbrainthefilm.com. is enlightening in unveiling the real reason Google has embraced this industrial scanning plan. Through a series of live interviews made with people directly involved with the project, mostly national or big library directors and technicians, it investigates its whole scope, still from the outside as Google hasn’t granted the authors any kind of insight. Actually is a matter of fact that corpus of Google Books is surely making their services technically better. The same Larry Page in the beginning defined Google not as the process of making a better search engine, but to make it an Artificial Intelligence. In the movie Ray Zurzweil confirms that, reporting a talk he had with Page about digitizing all knowledge and then develop true AI, which was centered on how books are important in this process, because of their very high quality standard.

Which is a strategy defined by Ted Striphas (previously author of the book « The late age of print ») in its book « Algorithmic Culture » : « Culture now has two audiences : people and machines » 13 medium.com..

If this is the large converging scale to consider culture as input for artificial intelligence, there are also efforts to independently digitize culture and make it free. Beyond the renowned examples like ubuweb 14 www.ubuweb.com. and aaaargh.com, in Italy finally the hacker community is being involved in the process of digitizing and sharing printed culture.

Among the others there are three interesting examples :

The Grafton collective in Bologna, scanning the Italian political cyberpunk culture of the nineties and sharing it on archive.org 15 archive.org.;

A huge archive of political magazines, poster and leaflets in Florence about leftist activism, called the « Archivio il Sessantotto » (Archive of 1968), slowly digitizing their archive;

The historical archive of one of the biggest national anarchic communities : the Germinal in Carrara, which built and used a DIY book scanner.

In 1869, the English literary critic Matthew Arnold affirmed that it was the purpose of culture to determine « the best which has been thought and said » 16 Arnold, M. « Culture and Anarchy », Smith, Elder and Co., London, 1869..

Is the kind of radical scanned knowledge mentioned before to be considered « among the best which has been thought and said », at the same level of Google selected content for its universal library ? It’s undoubtedly important for the related communities and almost impossible to find in institutional repositories. So in any case it’s remarkably valuable, whatever Google would think about it, and it’ll be freely accessible.

Agents vs. Media

Jeffrey Schnapp, ex director of the Stanford Humanities Lab affirmed : « the book is a construct in constant evolution : a construct that routinely and dynamically interacts with a shifting array of other media types. In other words, the book is a technology » 17 article online..

Looking back at how other media has been reflected into print, we can notice that traditional print has historically reacted in various ways to the various new media introduction throughout the 20th century.

When radio was gaining its momentum in the first decades as a new mass medium, there were examples of innovative synergies with print. For example, American Researcher Katie Day Good has found that in the 1920s the Chicago Daily News published several Radio Photologues 18 Day Good, K. Listening to pictures : Converging media histories and the multimedia newspaper, 2013., or travel diaries that could be listened through the radio and which were visually amplified through the pictures published on the same day in a dedicated section on the newspaper. Printed survived the introduction of radio, and what radio did was to induce a change in print, not to suppress it at any level, exactly as an agent of change would do.

TV was the next historical change in the mediascape, and in relation to print we have another outstanding example : the experimental paperbacks by Marshall McLuhan, Jerome Agel and Quentin Fiore. They embodied in the universal paperback format the TV synthetical information aesthetics and language, accumulating concepts and becoming in the definition of Schnapp « inventory paperbacks » 19 Schnapp, J. Michaels, A. « The Electric Information Age Book : McLuhan/Agel/Fiore » and the « Experimental Paperback », Princeton Architectural Press, 2012., envisioning a new way of structuring information on the printed page, reflecting the visual and perceptual changes.

More recently, in order to survive to the massive online competition even newspapers since a decade have included more data in their own visual structure than they ever did. It has been shaped in various graphic forms, from big figures to sophisticated infographics.

And in the contemporary print scenario, the above mentioned Print-on-Demand technologies have enabled the flexibility of digital in the printing process, in a new territory yet to be fully explored.

So print seems to have been deeply influenced by other media after their introductions, but to have then evolved accordingly. And if we look at audio and video, they have been also slightly influenced in the narratives and in technical specifications by other media, too, including the internet, but they still are mostly sequential in their own nature with the same original medial characteristics. In the end they have been conditioned, not reinvented. Then the main and difficult question can be : is internet a real medium, since it didn't invent completely new formats which were used by mass of people, or an agent, inducing radical changes in other historical media, but leaving their inner core intact ?

Conclusions

If we look at the use of software in journalism, we can see how it is leading in various sectors to the creation of completely artificial writing. An example is the ones created by the company Narrative Science 20 www.narrativescience.com., scraping information from the world of sport and business and narrativising them into news, after the parsing of dedicated algorithm. We can found similar experiments in generating academic papers (with the Babel Generator software developed at MIT) 21 www.businessinsider.com/babel-generator-mit-2014-4. and also in newspapers in the so-called « robot-generated » Guardian edition named « The Long Good Read » 22 See online, a collection of longform Guardian stories selected and laid out with the help of algorithms. But all these examples are once more reinforcing the fragility of the digital content versus the stability of the printed one, although implementing extremely interesting processes. So the historical role of paper to validate the content with its unchangeability is still intact and in a way it could definitely be interpreted as a stable virtue onto which to construct more complex processes.

This would be realized by the future creation of truly hybrid publications that would be able to mix running code and unchangeable content, integrating processes and stability in the same place. A hybrid of this type should be able to react to possible feedback from the processes it is able to trigger and to reflect it in its own structure. In this way we'd eventually be able to create a radical and distributed alternative to the centralized AI processes attempted by any of the few online giant.

In fact those kinds of processes would innovate processually, finally creating properly named « processual print », potentially influencing the society horizontally, with single persons being able to trigger cultural changes, and encouraging a completely new mixture of automatic and voluntary feedback.